Centralized Cloud Storage Risk Patterns: A Structural Taxonomy of Failure Modes

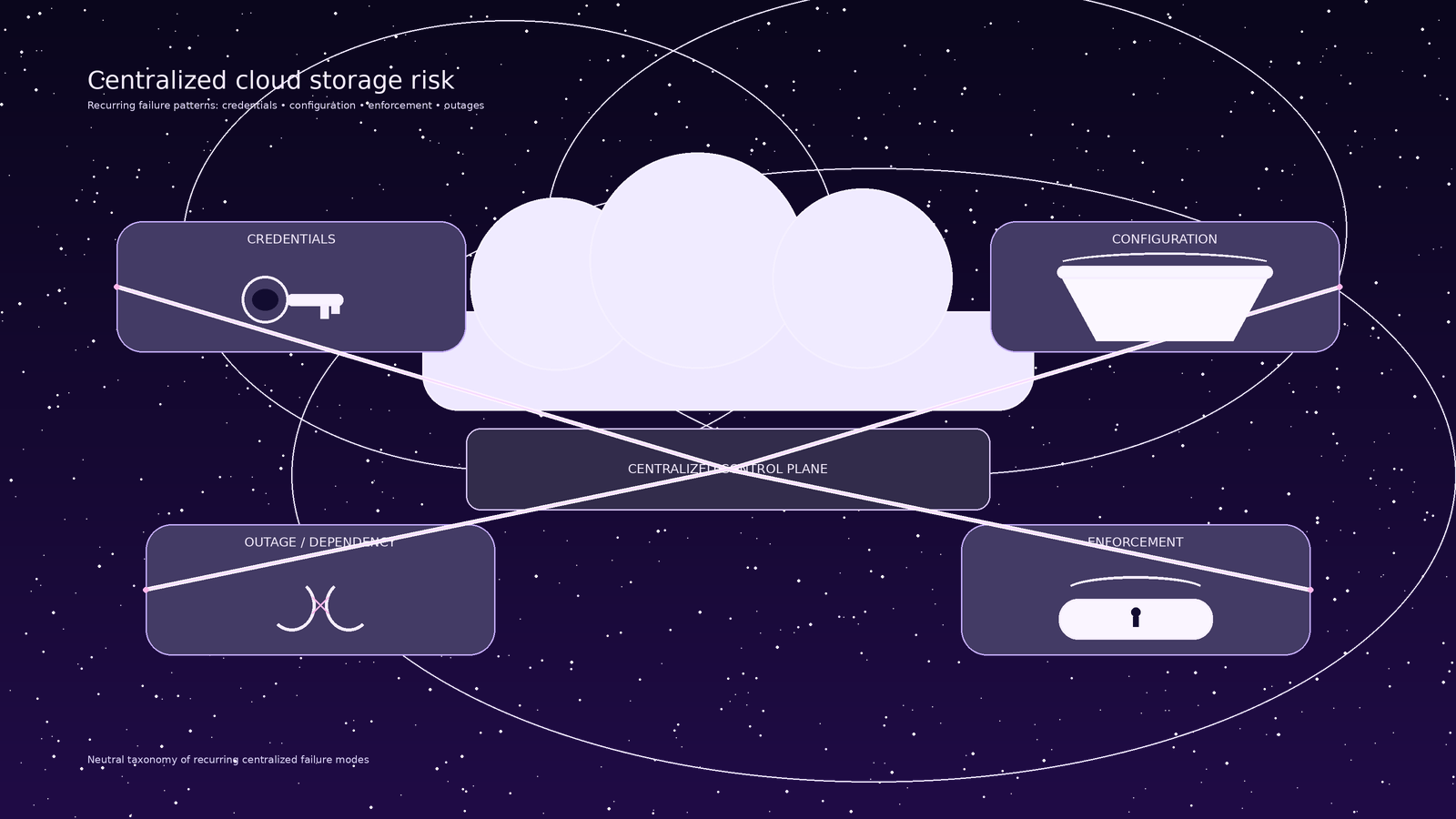

A neutral taxonomy of centralized cloud storage risk patterns, synthesizing breaches, misconfigurations, enforcement failures, and outages to explain why scale and central control magnify systemic risk.

Centralized cloud storage risk is evident in numerous public incidents, revealing recurring structural vulnerabilities. Across technical breaches, policy enforcement dilemmas, and major outages, common patterns emerge. These patterns involve systemic issues – single points of failure (like credentials or components), configuration oversights, discretionary controls, and scale-amplified failures – rather than isolated human errors. Below is a taxonomy of these risk factors, synthesized from high-profile cloud storage incidents.

Credential Exposure and Single Points of Failure

One recurring risk in centralized cloud storage is the compromise of credentials – passwords, access keys, or tokens – which often serve as all-powerful keys to vast data stores. History shows that a single exposed credential can have outsized impact due to centralized access.

Stolen admin or user credentials leading to breaches: In 2012, a popular cloud drive service exposed over 68 million user records after an employee reused a password that had appeared in an unrelated breach. Attackers accessed an internal file containing hashed user passwords, illustrating how one weak credential in a centralized system can compromise millions of accounts at once.

Similarly, in 2016, hackers accessed sensitive data on 57 million users and drivers at a major ride-sharing company after discovering hardcoded cloud access keys in a developer’s public code repository. That single leaked cloud credential provided access to an entire centralized data store.

These incidents underscore a core risk: when identity and access are centralized, a single stolen credential becomes a master key. There is often little granular partitioning to limit what a valid key can access.

Insider threats and privileged access: Credential risk is not limited to external attackers. In one major financial cloud breach, a former employee of a cloud provider exploited a firewall misconfiguration to obtain temporary cloud credentials. Using those credentials, the attacker accessed and exfiltrated data from dozens of cloud storage buckets, impacting over 100 million banking customers.

The root cause was an overly privileged cloud role combined with a network misconfiguration. Once access was gained, the centralized permissions model allowed escalation and broad data access.

Full administrative compromise: A dramatic example occurred in 2014 when attackers gained full administrative access to a cloud-hosted code repository service. After obtaining access to the provider’s cloud console, the attackers created hidden backup accounts and systematically deleted all cloud assets: storage buckets, databases, virtual machines, snapshots, and backups.

The service was unable to recover and permanently shut down. Nearly all customer data was erased. This incident illustrates the most extreme form of centralized failure: a single compromised administrator credential leading to total data destruction.

Structural factors: These incidents demonstrate how centralized cloud architectures concentrate trust in credentials. Cloud accounts and API keys often grant broad privileges by design. When leaked or misused, attackers gain immediate, wide-ranging access.

Scale magnifies the impact: one password can unlock millions of records. Practices like password reuse or embedding secrets in code become especially dangerous in centralized environments. Industry studies consistently show that stolen or exposed credentials are among the leading causes of cloud security incidents, closely followed by misconfigurations.

In centralized cloud storage, credentials function as single points of failure. A mistake or oversight involving one identity can cascade into a massive breach.

Infrastructure Misconfiguration and Open Access

Another major category of centralized cloud risk is infrastructure misconfiguration – improper settings that expose storage to unauthorized users or the public internet. Many major data leaks occurred not due to sophisticated hacking, but because centralized storage resources were simply left open.

Unsecured storage buckets and databases: One notable incident involved a database containing billions of records compiled by a cybersecurity firm. Although the data was aggregated for research purposes, the cloud repository was left unsecured with no authentication. Anyone could access and query the data.

In another case, a global consulting firm left multiple cloud storage buckets publicly accessible, exposing sensitive internal data including credentials, client files, and proprietary software. The data was world-readable and downloadable due to improper access policies.

These incidents show how a single configuration oversight can turn a centralized cloud environment into an open repository.

Cloud environment misconfigurations: Misconfiguration risk extends beyond storage buckets. In one long-running case, a major automaker disclosed that customer data had been exposed for years due to a misconfigured cloud database. The exposure went undetected for nearly a decade.

Similarly, a major financial breach occurred after a cloud firewall misconfiguration allowed an attacker to exploit server-side request forgery, obtain credentials, and download tens of millions of customer records from cloud storage.

Structural factors: Cloud misconfigurations rank among the most common causes of cloud data exposure. Centralized management consoles make it easy to deploy hundreds of resources quickly, but a single misconfigured asset can expose massive datasets.

Default settings, complex permission models, and scale contribute to persistent risk. Large organizations may manage thousands of cloud assets across teams and regions, making consistent configuration enforcement difficult. A single misconfigured resource among thousands can create a critical vulnerability.

The centralized convenience of cloud storage means a configuration error in one place can jeopardize everything stored there.

Policy Enforcement Failures and Collateral Damage

Centralized cloud storage platforms also concentrate discretionary control over user data. Policy enforcement errors – whether over-enforcement or under-enforcement – can have sweeping consequences.

Over-enforcement and false positives: In one well-documented case, a user’s entire cloud account was disabled after automated content scanning misidentified medical photos as prohibited material. Despite law enforcement clearing the user of wrongdoing, the cloud provider refused to reinstate the account. Years of personal data became inaccessible.

This case illustrates how automated enforcement systems, when applied at scale, can sweep up innocent users. Because cloud providers host data and enforce policy, a single mistaken decision can lock users out of all services simultaneously.

Under-enforcement and collective fallout: Conversely, insufficient enforcement can result in catastrophic platform-level consequences. In 2012, a widely used file-hosting service was seized by authorities due to widespread copyright violations. The shutdown abruptly cut off access for millions of legitimate users, many of whom lost access to lawful files stored on the platform.

Because the storage was centralized, users had no way to retrieve their data once the service was taken offline. Innocent users became collateral damage of the provider’s enforcement failures.

Structural factors: Centralization places providers in a powerful gatekeeping role. Enforcement decisions apply universally and at scale. Errors, overreach, or regulatory action can affect millions simultaneously.

Users have little control over enforcement outcomes. Their data fate is tied to provider policy decisions, automated systems, and legal pressures. These risks are structural, stemming from centralized governance and one-size-fits-all enforcement models.

Availability Outages and Scale-Amplified Impact

Perhaps the most visible risk of centralized cloud storage is large-scale service outages. When core components fail, access disruptions propagate widely.

Single error, massive fallout: In 2017, a routine maintenance error in a major cloud storage service removed more server capacity than intended, disabling critical metadata and allocation subsystems. For several hours, applications across the internet were unable to access stored data.

Because countless services depended on that single storage region, the outage affected websites, applications, and connected devices worldwide. Even the provider’s own status dashboard was impacted.

Core dependency failures: In another incident, a bug in a global authentication system invalidated user tokens, causing widespread service outages across storage, email, media, and third-party applications. A single identity service failure cascaded across an entire cloud ecosystem.

Structural factors: Centralized cloud infrastructure is efficient but concentrates risk. Shared platforms mean failures propagate rapidly. Hidden dependencies amplify impact, and recovery times increase with system scale.

While providers work to partition internal systems and reduce blast radius, users remain dependent on unified services. From a tenant perspective, failures remain centralized.

Conclusion: Structural Risks in Centralized Cloud Storage

Across credential compromises, misconfigurations, enforcement failures, and outages, the common thread is structural centralization. One element – a credential, configuration, policy decision, or subsystem – can become a single point whose failure cascades broadly.

These incidents are not isolated accidents. They reflect recurring failure modes inherent in centralized cloud architecture and governance. Scale magnifies impact, and trust is concentrated in a small number of systems and decision-makers.

Understanding these patterns allows organizations to assess cloud risk more realistically. Cloud storage failures are not merely technical mistakes; they are manifestations of structural design choices. Long-term solutions must therefore address architecture, governance, and control distribution, rather than focusing solely on individual errors.